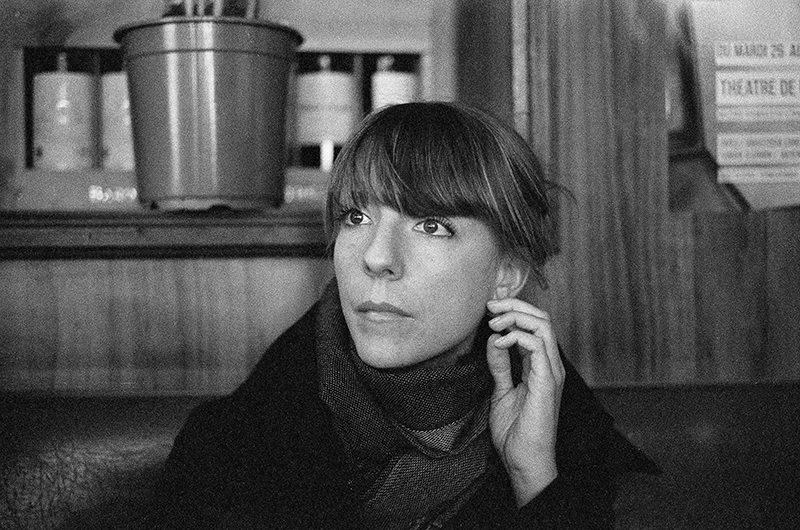

Last week I came across a beautiful image by André Kertész. Capturing urban life, Kertész (1894–1985) wanted “to make photographs as by reflection in a mirror, unmanipulated and direct as in life.” He has manifested himself as one of the more important photographers of the twentieth century.

Many obvious things are wonderful about the image. The lines. The composition. The clouds. The solitary man standing behind the semi-transparant glass, looking out at the an empty sea. All of it.

And what I also really enjoy about it, is the grain. So what exactly is grain, and why is it so appealing to me?

Grain

Photographic film often is a strip of transparent plastic film base coated on one side with a gelatin emulsion containing microscopically small light-sensitive silver halide crystals. Still following?

In processed film, the presence of small particles of metallic silver, or dye clouds, developed from the silver halide result in random optical texture: grain. Different types of film have different types of grain because the size of silver halide grains in the emulsion affects film sensitivity: larger grains give film greater sensitivity to light. That’s why faster film (= higher ISO) results in more grain.

Digital noise

When people buy digital cameras, they usually don’t worry about grain. That’s for the simple reason that digital photography doesn’t have grain. However, digital cameras do have an equivalent in their sensors: pixels. That’s why everyone’s fretting about megapixels and sensor size. The larger the sensor and its resolution, the less noise it will produce.

And for most, less noise is what you want. Because, if you would ask me, digital noise is something ugly and needs to be avoided. But I think film grain is beautiful. So what’s the distinction?

The difference

In case you missed the most important thing in the paragraph about grain, it’s the word ‘random‘. Pixels from a digital image sensor are the same size and are arranged in a grid. Film grains are randomly distributed and vary in size.

As the pixels of digital camera’s are set in straight lines – and with our brains hardwired to recognise patterns – they tend to annoy the eye of the viewer more that randomly arranged film grains.

To be honest, most likely you won’t see a lot of difference on a screen. But if you enlarge a digital file and compare it to a print of a blown-up negative, you probably will.

While some consider it a flaw – especially in the digital age -, the atmosphere which the grain’s aesthetic conveys is incredibly appealing to me.